Written by Curt Long, Chief Economist and Vice President of Research, NAFCU

How the Fed learned to stop worrying and love inflation

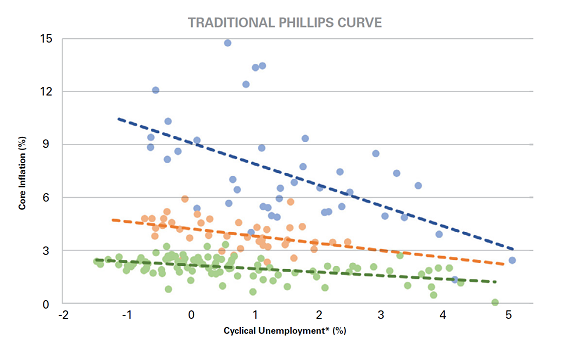

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, Congressional Budget Office

Last May, the current economic expansion became the second longest in U.S. recorded history. And barring a recession in the first half of 2019, it will overtake the decadelong expansion in the 1990s as the longest in history. During that time, economists watched with puzzlement as the unemployment rate dropped to a 50 year low, and yet inflationary pressures — the traditional dance partner of high-performing economies — were nowhere to be found. What ensued was a re examination of the classical framework for understanding the dynamics of inflation.

The Phillips Curve is a staple of any introductory macroeconomics course. Essentially, it describes what has historically been a close relationship between cyclical unemployment (that which goes beyond normal patterns of job gains and losses and is determined by economic conditions) and inflation. As unemployment falls near or below its “natural” rate, price pressures build, or so the theory goes.

And based on the evidence, the theory was a sound one until recently.

The chart above shows quarterly pairs of cyclical unemployment (actual unemployment minus the estimated “natural” rate) and inflation. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the relationship was a strong one, with periods of declining unemployment generally accompanied by higher inflation. But in the decades that followed, that relationship has weakened considerably.

Over that time, the economic model has evolved to take into consideration a couple of other important factors: past inflation and expected future inflation. Taken together, these have some important ramifi cations. By including past inflation in the model, economists are acknowledging a “stickiness” or persistence in inflation trends. The Federal Reserve (the Fed) has bemoaned how long it has taken to bring inflation from recession-era levels back to its 2 percent target. Meanwhile, the expectations component implies that economic forces that might ordinarily be expected to contribute to changes in inflation might be overridden by expectations. It is this feature in particular that economists are focusing on as they try to understand why inflation has remained so low recently despite historically low unemployment. To the degree that the Fed’s inflation target is credible, it could serve as an anchor to inflation expectations, and hence to current inflation.

The upshot is that inflation may not be as fearsome as it has been in the past, lurking in the shadows of every economic expansion, waiting to bring it to a premature end. Fed officials have given subtle hints that they may be adopting such a view. In an October 2018 speech, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell stated that “many factors, including better conduct of monetary policy over the past few decades, have greatly reduced … the effects that tight labor markets have on inflation.”

If that is the case, it presents a different set of questions for the Fed. On the one hand, there is less urgency to raise rates mid expansion merely to head off the threat of inflation before it has even appeared. Rather, it is inflation expectations that must be monitored closely. So long as they are stable, lower interest rates are not likely to result in an overheating of the economy. But any indication that public confidence in the Fed’s inflation target is diminishing would need to be addressed forcefully. It may be too late to incorporate lessons learned from recent years into the current expansion. But the next one is likely to see the Fed leave interest rates lower for longer, relying on the public’s faith that it will respond swiftly if price pressures do arise.

From the May-June 2019 edition of The NAFCU Journal magazine.

Related Content:

- Motivational Techniques, by Curt Long in the March-April 2019 edition of The NAFCU Journal magazine

- NAFCU’s Economic and CU Monitor (member-only)

- Macroeconomic Data Flash Reports (member-only)