Evidence from the field of behavioral economics

By Curt Long, Chief Economist and VP of Research, NAFCU

While economists have plenty to argue over these days, one thing that nearly all of them — not to mention employers — agree on is that we are in a tight labor market. In a recent NAFCU survey, our members ranked attracting and retaining talent as their second-most significant organizational challenge, behind only cybersecurity. And while finding and keeping the right people is key for any employer, keeping them engaged and motivated in today’s environment is no less difficult. With the abundance of opportunities for today’s workers, how can we keep them all pulling in the same direction? The field of behavioral economics has some ideas for incentivizing effort, and a recent study helps shed some light on its effectiveness.

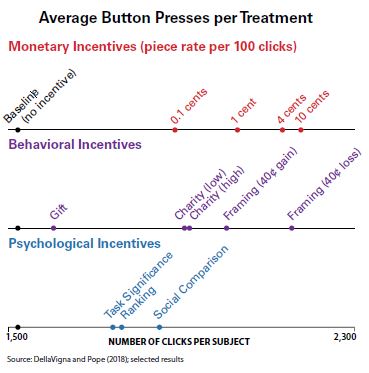

If economics is a study of our responses to incentives, behavioral economics mixes in a large dose of psychology to explore the ways in which real-life decisions may diverge from pure theory. In a much-discussed paper published last year titled, “What Motivates Effort? Evidence and Expert Forecasts,” researchers Stefano DellaVigna and Devin Pope devised an experiment in which hundreds of subjects performed a routine task — in this case, alternately pressing the “A” and “B” buttons on their keyboards as many times as possible for 10 minutes. The participants were each given different incentives, some monetary, others social or psychological, to see which levers resulted in the greatest effort from the test subjects. While each of these motivational strategies has been tested in individual studies, this was the first to combine them all in order to allow for comparisons between them.

And how did each treatment fare? It will come as no surprise that the most effective incentive was monetary. Subjects who were offered the richest incentive completed 43 percent more clicks than those with no incentives. Interestingly, the researchers found no evidence of crowding out. When workers are paid an extremely low rate (such as 0.1 cent per keystroke), it has been observed that effort often falls below uncompensated levels (thus the phrase, “pay enough or don’t pay at all”). The theory goes that workers find low-ball offers offensive, and their effort declines as a result.

Among the class of behavioral incentives, there were a number of notable findings. A gift was the lowest-performing incentive. Prior to the exercise, subjects were told that they would be given 40 cents regardless of their performance. The resulting work rate was just slightly higher than the baseline. Next, the researchers tested two charitable contribution treatments.

Intriguingly, the low-paying contribution (1 cent per 100 clicks) provided nearly the same incentive as the high-paying contribution (10 cents per 100 clicks). This is consistent with a “warm glow” model, in which charitable activity is determined by the emotion derived by the giver. The test subjects appeared to experience roughly the same “giver’s high” regardless of the amount of the contribution. Another treatment explored by the researchers was to use a threshold level of clicks which, when reached, would result in a 40-cent bonus. For some test subjects, the bonus was framed as a gain (“achieve this threshold and you will earn the bonus”), while for others it was framed as the avoidance of a loss (“your account has been credited with 40 cents, but you must achieve the threshold to keep it”). Consistent with other findings, the subjects responded more strongly to the loss-avoidance incentive.

Finally, some subjects were faced with one of three psychological treatments. In the first one, participants were told simply that it was important that they try their best (task significance). For the second treatment, subjects were told ahead of time that they would see how they ranked among other subjects after completing the task (ranking). But the top-performing psychological treatment was when the researchers told the subjects that other participants achieved a certain score. This social comparison provided a fairly effective (and costless) incentive. While it isn’t likely that employers will scrap their entire compensation structures based on these findings, they may prove helpful in targeted ways. Credit unions may also want to keep these strategies in mind when thinking about ways to boost member participation in surveys and referrals, for example. If nothing else, the field of behavioral economics affirms the complexity of human beings. To truly know your staff and your members — and what motivates them — is a strategic advantage

without equal.

This article was published in the March-April 2019 edition of The NAFCU Journal magazine.

Want to receive The NAFCU Journal in your inbox? Update your email preferences.

Related Content

- Pondering the Next Recession, by Curt Long.

Read more from the March-April 2019 edition of The NAFCU Journal magazine - NAFCU’s Economic and CU Monitor (member-only)

- 3 ways to develop internal talent, blog post by Dan Berger, NAFCU President and CEO

- Management and Leadership Institute